Bloodlust

Claire Denis’s Trouble Every Day

Well, that was odd, and surprisingly tame, given the film’s reputation (every week, the Cinematheque sends out an email to a mailing list detailing the week’s offerings; the listing for Trouble Every Day came replete with a warning about “Gory sex scenes and frequent nudity,”); I was expecting people vomiting in the aisles or something, but the film only inspired three people to walk out of a sold-out theater (the organizers again had to send people away from the screening due to the large crowd). Don’t get me wrong, the two scenes of gory sexuality and violence, were pretty disturbing (especially the last one, or as Jonathan Romney put it in his S&S capsule review from 2001 Cannes, “...suffice to say Gallo won’t be getting any offers of cunnilingus for some time to come.”), but come to think of it, The Piano Teacher, which did not feature vampiric, nymphomaniac cannibals, was a lot more disturbing. Still, the film’s reputation did inspire a bit of dread in me as I watched the film, which was a good thing, and disturbing in and of itself. I remember when Gallo, and his new bride, first entered their Parisian hotel (especially after Denis has Gallo fixated on the maid’s neck, demonstrated via close-ups) that I thought it was “too white,” and that could not be a good sign.

The film actually had a lot more in common with Denis’s last feature film, and the only other one I have seen Beau Travail. Like in that earlier film, Denis links repressed sexuality and self-loathing with violence; another parallel would be that instead of a clear narrative, Denis is more interested in setting a mood of quiet disturbance through visual beauty (again, kudos to Agnes Goddard’s camerawork). What little narrative there is simple, yet complex, principally because Denis conveys the story with pretty close to no exposition, a lot of editing ellipses, and sparse dialogue (and what dialogue that is actually spoken is delivered in a flat, monotone way, especially by Vincent Gallo, as if the act of speaking was a chore; and in any case, what is spoken is often mundane and repetitive). Most of the soundtrack is composed of ambient, natural noise or the wonderful, jazzy soundtrack by the Tindersticks (stylistically, much like Beau Travail which used excerpts from the opera Billy Budd, and some pop music).

Basically, Alex Descas plays a Parisian doctor and brain researcher named Leo, who has a wife, played by Beatrice Dalle (who competes with the tall, gaunt Gallo for “who looks the most strung out” award of the cast members), in a wordless, yet effective performance, as a feral woman, with a literally devouring sexuality. Somehow, Descas’s experiments have created this problem (referred to once in a while by the other characters as “a sickness”), and he works from his home, trying to keep his wife imprisoned in the house, who desperately wants to get out and have sex/eat her mates (at one point, she pulls out a reciprocating saw and cuts her way out of her top-floor bedroom). The other major plot strand, is of Vincent Gallo’s character Shane, who is an American pharmaceutical worker, ostensibly in Paris on his honeymoon with his waifish (and given her white and pastel colored clothes, somewhat virginal) new bride; but Gallo, has ulterior motives, he wants to meet Leo and discuss his research. Gallo’s characters go well beyond jet lag or sickness, as he struggles to control whatever it is, one by taking pills, and two, by constantly masturbating, instead of making love to his new bride (we later learn, that Shane stole Leo’s research, but we are left to infer that Gallo is suffering from the same malady as Dalle, and that is why he will not make love to his wife). After Shane fails to meet his Leo (though he does meet Dalle, who lunges at him, until he fights her off, and flees, as the fire that she set consumes the house). Soon afterwards, Shane returns to his hotel, and succumbs to his desires, tracking down the maid, who has frequently weaved in and out of the story.

This last scene is clearly the most disturbing. In a deserted changing room, Shane finds the maid, and they begin to have sex on the floor. But what starts out as pure lust, quickly turns into something more disturbing; she begins to resist his advances, and he pins her to the floor, causing her to cry out. What starts out as a rape quickly advances into something else, as Gallo buries himself in her crotch. She starts screaming in pain, and Gallo continues to pin her down, only to look up, with blood smeared across his face. This scene echoes an earlier scene between Dalle and a neighborhood kid who has broken into her house. She pins him down on the bed, taking control sexually atop him, before her kisses become literally hungry, as she bites his lips and neck, drawing both blood and screams, all of which seems to excite her more. Sex, food, and pain, all drawn together in some kind of inextricable matrix (given that our culture uses a lot of puns and food-derived metaphors when describing sexual acts, I can only surmise that the French do to). However, the film does contrast the progression of their illness. After Dalle sleeps with and kills the teenaged boy, she paces around the room in a blood-soaked nightie, in front of blood-smeared walls. Gallo’s Shane on the other hand, takes a shower, trying to clean off the blood (providing a chilling shot, bringing into question how much Shane’s wife really knows, as she spies a drop of bloody water sliding down the shower curtain after finding her husband, who, by the way, looks much more healthy after having sex/eating the maid).

Before I end this post, I wanted to remark on another similarity between Beau Travail and Trouble Every Day, that is Denis’s seeming fascination with abstracting the human body (especially the male body). While Beau Travail concentrated on the male form, in rest and in motion, in Trouble Every Day, during sex scenes, or scenes of nudity, the camera often pushes into extreme close-ups of writhing flesh. You see skin, but are disorientated, defamiliarized, forced to reconsider stuff you see every day. I just found that interesting.

AMC + Class Viewings For The Week

I hate writing about films before my time because I feel profoundly uncomfortable writing about something out of context (of course I never try to research it into context, but that's another story). Shroomy's convinced me to post on some of the older films I see recently, both on AMC and in a couple of my film classes. My first post of this got borked, so as well as excusing my poor, brief writings in the first place, this second post in even briefer and poorer.

Tartuffe (d. Murnau, 1926): D+

Murnau uses Moliere's play to make a film inside a film (which has gotta be a first for a film this early) about hypocrisy (specifically swindling money from wealthy people using a disguise). It is overwhelmingly simple in its themes and features some truly horrendous comic timing which stretches the 76min runtime to near infinity. Still, Murnau has a good dozen or so fine utilization of comedic close-ups, and Emil Jannings as a religious cult leader does all he can to be funny despite Murnau’s mishandling. Also has some interesting lighting, especially stylized candle lighting well before Barry Lyndon.

Rio Grande (d. Ford, 1950): B-

How’s this for a disclaimer?: I don’t like Westerns, the only other Ford I’ve seen is Grapes of Wrath, and I don’t like John Wayne. Still, this film was effective. The plot and the action were rather bland, but it has a very interesting theme on the duality of manhood between family and work/army/country/duty/whatever and carries some very subtle subtexts that should have been expanded on (especially how the mother/son relationship effects the father). Some terrific compositions, great performance by Wayne and some solid iconic imagery round the film out as a “coulda been.” Or maybe I need to see more Wayne/Ford/Westerns.

The Cheat (d. DeMille, 1915): B+

Highly enjoyable melodrama that could be disturbingly racist if the heroine of the film wasn’t actually much, much morally worse than the evil Japanese villain. Actually, despite superficial appearances the film isn’t all that racist at all, but the fact that heroic woman is actually more despicable than the principle rapist in the film is a fascinating cinematic decision, I wonder if it went unnoticed at time of release. Fun, if simple, costume/set coding to typify the principles, but what do you expect in 1915? Funky, dark, pretty racey for the time, pretty racist for our time, and wonderfully morally confused, this was a great silent.

I also saw Lubitsch’s The Student Prince of Heidelberg (1927), an absolutely superb romantic comedy of who’s details are quickly receding (I saw it about two weeks ago), but it is hilariously funny and very well made and has a darker, surprisingly realistic ending that totally threw me (and the class) for a loop.

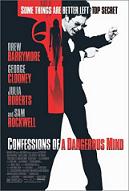

Confessions of a Dangerous Mind

Right from the get go by simply reading the title of the film Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, and from knowing that Charlie Kauffman’s script (warning enough) is based off of what Chuck Barris calls his “unauthorized autobiography”, there should be no doubt in a viewer’s mind that this film is going to be completely unreliably narrated. Confessions opens with Chuck Barris (Sam Rockwell), the creator of “The Gong Show,” “The Newlywed Game,” and “The Dating Game,” in a very poor condition, standing naked in front of a television, heavily bearded, alone in a disheveled apartment in 1981 where he starts narrating about what got him to this squalid point in life. One gets the feeling that Chuck is watching his own life on one of his own shows, the ones he was criticized for by showcasing freaks, weirdoes and idiots who just wanted to be on television, get their moments of fame. Apparently Chuck Barris, naked and distraught in ’81, isn’t all that different from them.

Barris’s opening narration explains that through most of his early years his life was focused on getting laid, a need that eventually led him to get hired in the television business, which, as well as being the wave of the future in the 60s, was also a great way of impressing women. Despite landing a steady relationship with Penny (Drew Barrymore), Chuck still hungers for more woman, more fame, more power, more anything. Evidently Chuck, as someone who was sex starved as a young man, has a serious void to fill in his life. On one side of his life he is trying to make it big in television, pitching the simplicity of “The Dating Game” to the execs at ABC (they decide to fund “Hootenanny” instead). On the other side is the mysterious proposition of Jim Byrd (George Clooney) who offers Chuck a job as a freelance CIA assassin as something “you do to relax.”

The real Barris, in his real unauthorized autobiography, asserts that he truly did work for the CIA, a claim that has since gone unproven. Director George Clooney ( Confessions being his debut film)  inserts short interview clips with real people who had contact with Barris during that time, including Dick Clark and the Unknown Comic, and all they can offer is sly hints that there may have been more to Barris than what they could see, and that sometimes he mysteriously disappeared for a couple days. Beyond that neither Charlie Kauffman’s script nor Clooney’s direction makes a firm statement as to whether or not this man in the film actually produced hit TV shows and was a hit man at the same time. Regardless, killing people conveniently inspires Chuck, who seems to get all his good ideas either after an assassination or while fantasizing about one (he comes up with the idea for “The Gong Show” when he fantasizes shooting a terrible guitar playing geisha during an audition). Both George Clooney, who plays Barris’s CIA connection, and Julia Roberts, who appears as a sexy operative, play their roles stiff and obvious, and there is almost a self-reflexive movie star-ness to them that makes all of Chuck’s CIA jobs seem like a flight of the imagination. On the other hand, Clooney forcefully keeps the style of the film consistent throughout ( Three Kings' DP nearly goes overboard playing with film stock, using graininess, washed out lighting, and blurry pastels to achieve a funky, surreal faded watercolor look to the film), not even taking a baby step forward to stylize Barris’s hits, so the possibility of Chuck actually killing these people (in the film) always seems a possibility.

The focus of Confessions of a Dangerous Mind must lie in the near inexplicable dichotomy of Barris’s life, because other than the CIA/TV producer angle his story is a typical Hollywood rise and fall seen in a million TV where-are-they-now specials. While Clooney’s style may be consistent, the film has further troubles keeping a steady, affective tone. Eruptions of the absurd seen to fit with the funky/grimy feel of Confessions’ 60s and 70s production. Examples range from a man cross-country skiing through the streets of  East Berlin is strangled in a car, skiis flailing widely, to when a contestant on “The Dating Game,” who wins over cameo contestants played by Matt Damon and Brad Pitt, turns out to be a high level KGB agent. But laugh out loud moments are painfully absent from this Kauffman script, which tries too hard to devote screeentime to Barris’s mental collapse without devoting any to what actually leads to it (the getting laid angle works only so far). It is understandable for a man who has to trick women into sleeping with him to trick himself into being a success, but the void in Barris’ life, the one he tries to fill with Penny, countless other women, television fame, money, and CIA operations, is never explained, nor is it ever filled. Confessions of a Dangerous Mind is a broad picture of a man’s need for something that he doesn’t know he wants, nor why he wants it. That makes the movie pretty hard on the viewer, but at least the Clooney’s direction is brisk, busy, stylish (in a slightly unpleasant, grubby way), occasionally funny, and often quite amusing. Confessions of a Dangerous Mind is an apt title only when one realizes “dangerous” really means “confused,” but then again that kills the mystique of such a quirky premise.

Oh Crap....Or My Feelings About Tonight’s Alias

Well, I’m having trouble getting to bed tonight, so I thought I would type out some thoughts regarding the apparently new direction that one of my favorite shows has undertaken. Have you ever felt a simultaneous elated and sinking feeling? Well I have. While excited that the critically acclaimed, yet relatively little watched Alias (apparently by ABC standards, 9.3 million viewers per show is relatively little watched), was given the prime, post-SuperBowl time slot, I actually had little faith that the increased exposure of the show would translate into substantially more viewers because the rigorous backstory, continuity, and serialization that show has displayed over 1 and 1/2 seasons would make it difficult for new viewers to acclimate to the show without consulting some Internet episode guides, something I don’t see many people doing. Then I heard that this new episode would be “more accessible,” to new viewers. Hmmm. Then I read that the producers, who may or may not be bowing to the demands of the ABC programming executives, had decided to take the show on a different course, de-emphasizing the cliffhangers and serialization in favor of more stand-alone, episodic plots. OK, I could live with that, as long as continuity and backstory were maintained. But nothing could prepare me for the radical changes that the show’s creator, JJ Abram, had in store for me. Perhaps, I had become overhyped on this particular episode, I mean prior to the viewing, I had read a glowing, four-star review from Herc, the TV reviewer at AICN, as well as seeing the TV spots championing the new episode with the excellent reviews as it’s centerpiece (well that and Jennifer Garner in sexy clothes). I waited for it breathlessly.

I was actually, kind of surprised and worried at the lack of a “previously on Alias” segment that usually proceed the show (and which sometimes run several minutes long). It started out well, with Jennifer Garner modeling sexy lingerie for some obese French-guy to the tune of AC/DC’s “Back in Black,” before the espionage action kicked in. The show even indulged in one of it’s favorite narrative gambits: starting in media res with one of Syd’s missions, and then flashing back to the past to fill us in on the details of what led to the opening situation. This is where the sinking feeling began to creep in. As the flashback began, I was subjected to scene after scene of exposition regarding events I was already familiar with, which I accepted at the time as necessary for new viewers, but to me felt like Alias for Dummies (at least they made it narratively plausible). But everything felt rushed, instead of the obvious, yet repressed romantic desire between CIA handler Vaughn and his double agent Sydney, we get Vaughn dragging Sydney into a side room and laying it all out on the table, even though he said almost the exact same thing in the last episode, just not so blatantly. Hey, I don’t mind, I like the Vaughn-Sydney romance, at least, I liked it before; I’m a romantic at heart, but I don’t like it easy on my couples (hence my love for the relationships between Buffy-Angel, Buffy-Spike, and John Crichton-Aeryn Sun). But this rapid turn of events was nothing compared to the totally out of left field, developing romance between Sydney’s best friends Will (now recruited by the CIA) and Francie (once the only “normal” character on the show). That left me scratching my head, but since the characters were as confused by this new development as I was, I let it slide (it would have been more out of place earlier in the series, since they were setting up a Vaughn-Sydney-Will love triangle for a while). The only new development was that Arvin Sloane, the head of SD-6 was MIA, and that the Alliance had replaced him with a man named Geiger, played by Rutger Hauer (some catch-up for non- Alias fans; the Alliance of 12 is a rogue espionage organization with twelve individual cells which pass themselves off as black ops divisions of the CIA, the one headed by Sloane, at which Sydney, and her father, Jack, work is called SD-6; in a brilliant subplot, Arvin Sloane was able to whisk his wife away to freedom, as well as get away with $100 million of the Alliance’s money).

Geiger’s arrival prompts some anxiety among the duped members of SD-6, but especially Sydney, who gets grilled by Geiger over the death of her fiancé (he was killed by the SD-6 Security Section on orders from Sloane, because Sydney revealed to him that she worked for SD-6). Sark, once an agent of “the Man” (who actually turned out to be Sydney’s mother), now working for SD-6 tips off Sydney to the existence of “Server 47,” a top secret Alliance computer containing all of it’s secrets; to make matters more interesting, the Alliance keeps the crucial Server 47 on a 747 which never lands except to refuel, as well as pick up the call girls for the computer expert on board. And with a little planning from the CIA, we find ourselves back at the beginning of the episode. Up to this point, I was pretty much A-OK with how things were going, with a few, already noted exceptions. There was plenty of action, and things were moving along at at the typical clipped pace. Then came the bombshell, with the information gleaned from Server 47, the CIA could take down the Alliance, all of it, if they could only confirm the intel, and to do that, they need the security code from the SD-6 computer. Jack, who was pretty much second in command to Sloane, volunteers, but is waylaid by Geiger and Security Section. While Jack and Sydney were at the CIA Command Center, Geiger had the techs break into Sloane’s erased files and recreate some data, which indicated that Sloane knew all along that the two of them were double agents (I guess Sloane wasn’t as dense and/or naive as I had previously thought). Jack is able to tip-off Sydney that he has been captured by SD-6. They have to think fast, Kendall, the director of CIA operations won’t move his agents into position until they’ve verified the intel (they need to disable the security systems or there would be massive civilian causalities from the explosive charges laid into the foundation of Alliance buildings), so Sydney turns to her partner, Dixon.

Sydney’s continuing lies to Dixon, who remained steadfast in his belief that SD-6 was part of the CIA and that he was doing good for his country, have been a focal point of their relationship, which is almost father-daughter. It’s been strained, Sydney continually wanted to bring Dixon in from the cold, and eventually, Dixon’s suspicions became aroused, aroused enough for him to report to Sloane that he thought Sydney was a double agent (Jack covered it up for Sloane). A tearful Sydney tells Dixon the truth, which was a very well done, emotional scene, as to be expected. Dixon doesn’t entirely believe her, but he trusts her enough to follow her instructions, and his worst fears are confirmed. SD-6 is part of the Alliance. Devastated, he gets the information that Sydney needs but hesitates, even calling his wife, almost as if for the last time. And while all of this is going on, Jack is being tortured by Geiger with a car battery and some jumper cables (I’m not sure what it is, but for some reason, every show I really like has displayed torture in some form, it’s kind of weird, and scary). Eventually, Dixon e-mails the info to Sydney, which confirms the Intel that they gleaned from Server 47. This is where, I think the show took it’s biggest risk, and may have even sown the seeds of it’s destruction.

The CIA and other allied intelligence agencies launch a series of raids against all twelve of the SD cells, as well as the Alliance HQ and member’s homes. It’s a furious action scene, with CIA agents battling Security Section, and just as Geiger prepares to kills Jack with some more voltage, Sydney rushes into the examination room and kills Geiger There raid is a complete success, the Alliance and SD-6 is destroyed. The ENTIRE PREMISE OF THE SHOW HAS BEEN ACHIEVED IN THE MIDDLE OF THE SECOND SEASON. Whoa, I don’t know about that creative decision, something that major always inspires some trepidation on my part (even if it seems to be a popular choice these days among my favorite shows; a recent episode of Angel featured the destruction of the series long-standing villains, the evil law firm Wolfram & Hart, while two recent episodes of Farscape found John Crichton returning to Earth). Of course, the destruction of SD-6 allows Vaughn and Sydney to consummate their relationship in one long kiss, with swirling cameras and a befuddled, comic Agent Weiss. Well, there’s another premise of the show gone as I thought the show often thrived on the sexual tension between Vaughn and Sydney, but now that their relationship can be somewhat out in the open, I’m not sure it can be as sexy, dangerous, complex, or exciting as it once was. But I guess we’ll have to wait and see.

And actually, I would be totally howling in protest right now if it wasn’t for the last two plot twists (well three, one of the most interesting developments was Dixon’s anger at Sydney’s portrayal.) Well, it turns out that Sark and Sloane where orchestrating the destruction of the Alliance to further there own goals, by feeding the necessary information to Sydney and Jack. And now they are ready for what they call “Phase Two.” Cut to Francie talking on the cell phone to Sark. I’m like, “oh shit,” as the camera pans to the left, a trail of blood smeared on the white wall of Francie’s restaurant. My first thought was “They killed Will, you bastards!” but to my relief/horror, it was Francie’s body with a bullet through the forehead. Well, I guess that leaves absolutely no normal characters left on the show. Everyone is an agent now.

Oh yeah, it’s a new beginning all right. I’m guessing that Sydney and Jack will openly work of the CIA now, so no more double agent stuff (which was actually beginning to strain the show’s credibility, which was a perverse statement, in and of itself), and the Vaughn/Sydney relationship will be opened up (bye, bye Alice), unless they find some reason to backpedal. JJ Abrams has essentially hit the eternal reset button by destroying the Alliance so early, even if he keeps continuity by having Sloane assume the role of ultimate villain. And of course, there is the entire issue of Irina Derevko’s (aka Sydney’s mother) loyalty and the Rambaldi stuff for the show to resolve. Fertile ground, yes, but can the writers of Alias continue to weave such a complex and compelling tale with such great changes to the storyline? Rationally thinking about it, I can say yes, but I can’t ignore this feeling in my gut that says a year from now, I’ll be cursing this episode, which, on its own terms was actually pretty good (even though it felt rushed and the material should have been expanded to a longer episode, or the now “forbidden” multi-episode arcs). I hope I’m wrong.

As a side note: Man, did the SuperBowl commercials really suck this year or what? The only one I can remember right now is the FedEx commercial that parodied Cast Away. That was pretty funny.

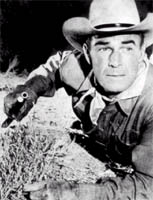

Seven Men From Now

I love Westerns. They are an action-orientated genre, which, for better and for worse, capture a national myth, while usually exploring often intertwined subject matter of interest to me: the American cult of violence, masculinity, sexuality/gender, and race. Add to that, the fact that genre has attracted the attention of some of classical Hollywood’s best directors, and you get a large and vibrant cross-section of films, many of which are stylistically, narratively, and morally complex (as a side note: moral complexity has become more and more important to me; not so much the answers or easy conclusions, but the moral complexity of the situations themselves). Most film aficionados have heard of such great Western directors as John Ford and Howard Hawks, and the more knowledgeable Western aficionados are well aware of such luminaries of the genre as Anthony Mann and Samuel Fuller. The really, really knowledgeable usually mention the director Budd Boetticher (pronounced Bet-ick-her) in the same breath, though his films are much harder to come across than the others.

Between 1956 and 1960, Boetticher, then best known for his bullfighting films, directed seven B-movie Westerns starring Randolph Scott (as he got older, I think Scott looked and sounded more and more like Gary Cooper), which were known as the Ranown Cycle, so named after the production company of (Ran)dolph Scott and Columbia producer Harry Joe Br(own). Five of these movies, including the first of the series, Seven Men From Now, were written by screenwriter and future director, Burt Kennedy (despite being lumped in with the Ranown Cycle, Seven Men From Now was actually produced by John Wayne’s Batjac Productions for Warner Brothers). Each semester, the UW Cinematheque features a retrospective of a particular directors works, and I’m glad that this time they chose Boetticher, a director I’ve always been curious about; they will be showing six of the seven Ranown films (the only one they won’t be showing is Westbound) as well as his 1951 film The Bullfighter and the Lady.

While I was thinking about this movie, I was reading through some of the few sources I have on Boetticher, who was a particular favorite of André Bazin. I came across Andrew Sarris’s Boetticher entry in The American Cinema, and I think one passage really captures something about the Boetticher film that I saw last night:

”Whatever his action setting, be it the corrida, the covered wagon, or the urban underworld, Boetticher is no stranger to the nuances of machismo, that overweening masculine pride that provides both a style and a fatal flaw to his gun-wielding or cape-flourishing characters. Boetticher’s films strip away the outside world to concentrate on the deadly confrontations of male antagonists. No audience is required for the final showdown. It is man to man in an empty arena on a wide-screen before a very quiet, elemental camera. Elemental but not elementary. Boetticher’s timing of action is impeccable. He is not a writer-director like Burt Kennedy or Sam Peckinpah, but he is a much better storyteller.” (pg 125)

Elemental is correct, in the tight, compact 77 minute running time of Seven Men From Now Boetticher sometimes makes Howard Hawks look like Max Ophuls, as the camera does not move much. Despite taking place on the frontier (it was shot in Texas), and employing a widescreen frame (as well as color photography), there is not an extensive usage of Fordesque vistas, instead much of the action takes place in rather cramped quarters, such as the interior of a ponderosa wagon, or in the various caves, crags, and crevices that characters use to take shelter. Even on the open prairie or in the desert, Boetticher employs tight framings, often in close-up, of one or two characters, and uses shot/reverse shots instead of a roaming camera. Silence is another frequent motif of the film, as the main character, Ben Stride virtually defines stoic; even though there actually is a lot of talk in the film (as Paul Schrader said in an article in Film Comment about the rerelease of Seven Men From Now, which was considered lost for many years, “talk is cheap.”), but there are many, more memorable sequences in the film, where little, if nothing is said.

The film begins with a flash of lightning and a bolt of thunder. It’s night, and a thunderstorm is soaking the landscape. The credits and theme song, a ballad about revenge, plays, before an unknown man, face turned away from the camera, walks through the muddy landscape. He spies a campfire and walks over to it; underneath a rock outcropping, two men are taking refuge from the rain. Sipping coffee, they meet the stranger who is revealed to be Randolph Scott’s character (named Ben Stride) warily, who asks if he can join them and get out of the rain. The younger one seems to want to run away, but the older man keeps his cool. Talk turns to the nearby town of Silver Springs. There was a robbery, seven men held-up a Wells Fargo station, and in that robbery, a woman was killed. All seven men got away. The older man says “That killin’, they ever catch up to them fellas that done it?” Stride simply replies “Two of them.” The two men grab for there guns and Boetticher cuts to a pair of horses lashed to a tree; gun shots ring out, scaring the horses.

The film parcels out little of Ben Stride’s motivation, at least at first. It’s clearly revenge, but we don’t really learn what is driving Stride until later in the film. We learn that Stride was once the sheriff of Silver Springs, but after 12 years, the citizens held an election, and Stride lost. He was too proud to become merely a deputy and could find no other work befitting an ex-sheriff, so his wife took the job at the Wells Fargo station, and it was she who was killed by the bandits. Now, Stride will not rest until all seven men are dead.

While the revenge story is the main thrust of the plot, two other narrative strands are introduced later in the film. After Stride kills two of the bandits, he takes their horses and rides towards a town called Flora Vista. Along the way he meets up with a wagon that has become stuck in the mud. John Greer and his wife, Annie, are the owners of the wagon, and they are heading from back East to California. Right from the start, the movie counterpoints the capable, stoic Stride with the rather helpless John Greer, who while, affable, just talks and talks and talks, instead of getting things done. After helping them out of the mud, Stride prepares to ride off, but Greer asks if he will ride with them to Flora Vista, rather fateful decision (and probably the right one, Greer is clearly out of his element in the West). It’s fateful, because Stride almost immediately becomes attracted to Annie (Gail Russel).

The third major plot strand is the introduction of the charismatic, ambiguous, outlaw Bill Masters, played by Lee Marvin, and his sidekick, the monosyllabic Cleet. Also from Silver Springs, Masters knows the truth about Stride (and it is he who shares it with the Greers, and the audience), as well as the fact that the seven men have stolen $20,000 in gold from Wells Fargo, and he’s out for the gold, and willing to help Stride, to a point (we learn that two times, while Stride was sheriff, he locked up Masters), even saving Stride’s life by killing one of the seven men (the fourth, and least important subplot of the movie, is a group of “marauding” Apaches, who are simply looking for food and have taken to attacking small bands of travelers; a war party is chasing one of the seven men, and Stride and Masters ride them off, as Stride turns to get the man’s horse, the outlaw draws his gun, but is cut down by Masters). Bill Masters is almost like an evil twin of Stride (he wears a black hat to Stride’s tan one); he’s as equally well mannered as Stride, though there is a twinge of mocking irony to his politeness, as if that kind of chivalry is as out of place on the frontier. Still, Masters shares much of the same masculine ethos as Stride, “the put up or shut up” kind of attitude that they share. But more importantly, Masters too finds himself (sexually) attracted to Annie Greer, and he also notices the growing attraction between Stride and Annie. It becomes clear as the group rides on, how in effective John really is. Stride pretty much keeps his reservations to himself, but Masters readily voices his own, calling John “half a man.” Soon thereafter, Annie and Ben are doing the laundry together, and talk turns to John Greer, and his lack of ability to provide for his wife. Annie Greer begins to mount something of defense for her husband, and somewhat rhetorically asks Ben, “Do you think I love him any less?” Somewhat, unexpectedly, and with a voice tinged with anger, Stride replies with a curt “Yes.”

This scene comes before one of the key scenes in the movie. Again it is night, and it is raining. Cleet and Masters are on watch; the Greers and Stride have taken cover inside the wagon. Masters decides to get himself a cup of coffee, and finds the other three sipping coffee silently inside the wagon. We get a master shot of all four of them, with Masters and John in the rear of the wagon, and Annie and Stride in the front. Noting the growing tension between the three of them, Masters begins to tell a very thinly veiled tale which is clearly about the growing attraction between Annie and Stride. Boetticher frames the four of them into three groups, cutting back and forth between them emphasizing the figurative distance between them: a close-up of Masters telling the story, a close-up of John with a pained expression on his face (he may be helpless, but he’s not stupid, and more importantly, he really doesn’t say much of anything in this scene), and a two-shot of Annie and Stride. Eventually, Stride tires of Masters needling (or perhaps he doesn’t like his true feelings mirrored in Masters and his story) and drives him and Cleet off. They ride off into the night for Flora Vista. John takes watch, and Stride clambers underneath the wagon to his bed roll; above him, Annie stretches out in her petticoat and corset, separated from Stride only by the wood planks of the floorboards (if it wasn’t for the floorboards, she would be laying directly on top of him). Though the two of them don’t say much, it’s a rather suggestive scene.

Masters and Cleet ride into Flora Vista where they meet up with the surviving four gang members. In return for a portion of the money (though I’m sure they intended to double-cross the gang), Masters reveals where Stride is and when he will be arriving, in turn, the leader of the gang, Bodeen, reveals that they hired John Greer to transport the strongbox with the gold from Silver Springs to Flora Vista. Back at the Greer’s wagon, Stride prepares to leave, knowing what he will face in Flora Vista, and not wanting to endanger the Greers, at least, not Annie. Annie hands Stride a neatly folded shirt, and the two of them impulsively, almost kiss, pulling away only at the last minute. Stride rides off to finish his revenge.

Stride rides through a rocky canyon, where he is ambushed by two of the gang members. Shot in the leg, Stride scrambles into the rocky outcroppings, and takes a position in a small crevice, playing a dangerous game of hide and seek with the two outlaws. Still, they are no match for him, and he kills both of them as they tried to position themselves for another attack. Stride, now wounded, and with his horse having run-off, tries to capture one of the outlaw’s horses, but is knocked out in the process, to be found by the Greers later in the day. They help him out, with Annie tending to his wounds, not knowing if he will make it. She wants John to ride ahead to Flora Vista and fetch a doctor, but John reveals that he can not go to town without the wagon, finally confessing to his wife that they are carrying the strongbox, but denying that he knew of the larger implications of his actions. Stride awakes and makes John throw the strongbox off the wagon, and then shoos the two of them away, but before they leave, John hands Stride his rifle.

In town, Bodeen and the other surviving gang member wait in the saloon with Masters and Cleet. They hear the wagon approach and go outside; Masters and Cleet wait up on the porch of the saloon, as Bodeen and the other man go talk to them. John tells them that he doesn’t have the money, revealing that Stride took it in the canyon. Bodeen and the other prepares to ride off to confront Stride. John knows what he must do, not only to prove his manhood and repay the debt he owes Stride, but also redeem himself in the eyes of his wife for the moral stain of helping the outlaws. He gets off the buckboard, and begins to walk towards the Sheriff’s office, which is at the end of the dirt street; however, between the wagon and the sheriff station stands Bodeen and the other gang member. John walks confidently, standing tall, and most importantly, at least thematically for the film, he walks in silence, saying only a few words first to his wife (knowing that he is most likely to be killed) and then to Bodeen. He simply shrugs them off and continues to walk towards the sheriff’s office, only to be shot in the back by Bodeen. Annie and the townspeople rush to John’s body, as Bodeen and his henchman ride off. From the porch, Masters wryly remarks to Cleet that maybe John “wasn’t half a man,” before they too ride off for the gold.

Bodeen and his henchman arrive in the canyon, to find the strongbox in the very center of the wide canyon (the rocky canyon walls are almost like a natural amphitheater, or befitting Boetticher, a corrida). Clearly, it’s an ambush set by Stride; the two of them develop a plan to rope the strongbox and ride off with their money, but the henchman is quickly cut down by a bullet fired by an unseen shooter. The death of the henchman drives Bodeen into the rocks, where he is cornered by Masters and Cleet, and shot down. Shockingly, Masters turns on Cleet and shoots him dead also. In a tense scene, Masters walks down to the strong box, and is joined by a limping Stride (who uses Greer’s rifle as a crutch). Masters wants the money and Stride won’t let him have it. They face off, exchanging a few quick words, some about Annie and her new widowhood, but soon the two men lapse into silence, as they wait for one or the other to draw (both men have displayed their gun prowess throughout the film). Boetticher’s camera cuts back and forth between Stride and Masters, separating them into their own frames. The camera rests on Masters for a few beats longer than normal, and then he goes for his gun, but there is an off-screen gun shot. Stride has killed Masters.

Soon thereafter, in Flora Vista, men from Wells Fargo load the strongbox onto a wagon as Stride watches over them. He turns to a waiting stage coach; Annie, dressed in black exits from the hotel. Stride tells her it’s a good idea that she is going to California and that he is returning to Silver Springs to take that job as deputy. He bids her farewell, and rides down the dusty street. Annie watches Stride as he rides off, and the suddenly orders the stagecoach driver to remove her bags. She doesn’t plan on going to California just yet.

|