Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle

With its brain-dead amateur direction, witless script, impossibly sloppy special effects, non-existent videogame-like narrative, empowered female stars traipsing around in seven dozen wigs and skimpy outfits, and a color palette that has enough filter-fueled crackle and zing to top anything Technicolor’s ever done for cinema, Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle successfully bombards its audience with enough screaming noise and constantly moving eye-candy to partially satisfy even the most cynical and scoff-happy cineaste. Neglecting any of the qualities that could make such music video cum feature length pop exploitation enduring-namely semi-intelligent camp, or inventive forms of sexuality and/or violence-newest hack director McG manages to sneak one by the intelligentsia and make his film successfully engaging in an utterly inexplicable way. Haphazardly strung together are motocross racing, surfing, the Mongolian army, burlesque strip teases, Demi Moore, a wise cracking Bernie Mac replacing the unfunny Bill Murray from the first film, a hilariously un-Irish Irishman played by Justin Theroux (the young movie director in Mulholland Dr.), the Return of the Thin Man, and the Angels as (among others) dock workers, nuns, dripping wet, a Mongolian gambler, and a bull riding Swedish tourist. The movie is oddly not nearly as goofy or tongue-in-cheek as it should be (though it amusingly jabs the 2000 original by mocking the rumored 13 screenwriters that churned out that atrocity), but McG’s epilepsy inducing editing races the film by so quickly that it causes one to stumble out of the theater with a dumb, dazed half-smile on their face and little memory of the past 24 hours. Sometimes that’s a good thing.

Whale Rider

Writer/director Niki Caro’s adaptation of Witi Ihimaera’s Maori fable Whale Rider seems to have the deck incredibly stacked to its advantage. Utilizing location shooting on New Zealand’s pristinely beautiful landscapes (the ones that double for Middle Earth in Lord of the Rings), featuring a story boiled down to classical archetype, and introducing the formidable acting talent of adorable thirteen-year-old actress Keisha Castle-Hughes, the setup seems prime for a humbly epic tale of an ancient tribe’s modern tribulations. Sadly, such a well-meaning film contains little of the crystalline focus required for this kind of pure and beautiful tale. Castle-Hughes plays Pai, a Maori with the blood of leaders in her veins, but who was unfortunately born a girl, negating her from the Maori tribal custom of male leaders, a custom rigorously and blindly held by her grandfather Koro (Rawiri Paratene). Pai’s father has gone abroad to forget his Maori roots and his wife who died in childbirth, entrusting Pai’s rearing to her grandparents. Whether Whale Rider is about an ostracized young girl coming of age, Pai’s resolute traditionalist grandfather opening his eyes to reality, or a fractured and dispirited tribe trying to find new beginning is never made clear. In keeping the film’s narrative arc to its most pure and its cast to the bare minimum Caro neglects many of the elements that make Whale Rider have the ability to rise above its classical setup, namely its Maori setting, and Pai’s father’s relationship with the family and the tribe. The Maori community that Pai is supposedly suppose to lead (if she obtains the ability to overcome her gender) is almost nonexistent in the film, and consists of a few brief pictures of young male children, a couple town elders, an a half dozen lazy 20-somethings. Similarly, the oppression in Pai’s household that comes from the nearly sadistic grandfather appears to be something Pai already understands and can live with; where she is at the beginning at the film and where she ends up at the end, in terms of maturity, is a mystery. Solid one-note acting, a charismatic new actress, and glacially clean wide, wide, cinematography is not enough to distract from Whale Rider's failings, but it certainly helps make the film a passably enjoyable experience.

Sunrise

Murnau’s masterful 1927 silent feature, subtitled A Song of Two Humans, strives to work as pure allegory when its lead, The Man (George O’Brien, as confused and burly as a countryboy should be), is tempted to kill The Wife (Janet Gaynor, sweet and beautiful, as all milkmaids are) in order to move out of his farm house and go to the magical metropolis across the lake in the arms of The Woman From The City (Margaret Livingston, as the kind of urbanite who forces her peasant innkeepers to wipe the dirt from her boots). The film is rigidly broken into three very different acts; the first features The Man’s hideous decision to drown his wife and his eventual decision to re-embrace her love, he then pursues The Wife, now stricken with fear, into the City to beg his forgiveness; the second act is their urban reconciliation where they dreamily get their picture taken and visit a grand carnival out of a happier version of Metropolis, in an urban dreamland where a peasant’s ability to catch a loose pig and then dance a rural jig earns the admiration of the upper-class; the third act is the couple’s return to their home and results in a final test of love when a storm strikes and threatens to kill The Wife in the same way The Man was originally planning to. Though Murnau has obvious trouble smoothing the tone switch between the acts of the film, which was scripted by Kammerspiel mastermind Carl Meyer (who also did Murnau’s triumphant The Last Laugh), Sunrise is an overwhelming displays of the director’s awe-inspiring visual capacity, with flawless special effects, subtle expressionism and tremendous application of Fox’s resources in creating a movie filled with detailed miniatures, dramatic camera movement, an immense set used as a working metropolis, and a simple lyrical poetry to back up its marvelous technical triumphs.

Capturing The Friedmans

With a heavy sigh of relief the clichéd tradition can be retired of invoking Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon every time a movie features an investigation from different perspectives. Andrew Jarecki’s documentary for HBO, Capturing The Friedmans, does nothing as simple as retell the same event from a handful of views; Jarecki structures his documentary like an organic, ever evolving and dynamically changing entity, and through his marvelous film it seems that what truly happened within the Friedman family will always be a matter of debate.

An outwardly normal upper-middleclass Jewish family, the Friedmans suffered a shock in the mid-80s when  the family’s father Arnold and one of his three sons were accused of pedophilia. In a unique bit of luck, the family’s oldest son David videotaped several family interactions between the time the charges where brought and the sentences were carried out. Jarecki intercuts this footage with a large amount of far more innocent home movies of the Friedmans when the sons were children and more carefree, as well as tracking down and interviewing a plethora of those involved with the case more than a decade ago, including lawyers, the judge that heard the case, several victims, and officers of the sex unit division of the Friedmans’ small town. Aside from the peculiar but accepted fact that the Friedmans spent an unusual amount of time documenting themselves, both before and during their crisis, Jarecki’s film is an unsettling revelation of how perception varies, and the implications of this on the justice system, public scrutiny, and the documentary genre that this film adheres to.

As Capturing The Friedmans moves forward, charting the family’s story chronologically, Jarecki peppers the story with the insights of various outside observers as well as from the mother and two sons (the father recently died in prison and the middle son refused to take part in the film), and Jarecki structures it in such a way that each time someone speaks-be it a shadowed victim describing the crimes, or the Friedman matriarch struggling to explain the strange new dynamic between her sons and her husband after the crime went public-the entire picture needs to be reevaluated. And then someone will speak again and  flip the whole picture up side down. What comes to light is as hideous as it is complex, and as distorted as it is poignant. There are dozens of unexplainable layers to the Friedmans’ story that are touched upon in the film, from the nature and background to the crimes themselves, to deep-rooted problems within the family structure and how these eventually led to the behavior during the family’s crisis. What results is an incredibly engrossing story that seems to have no end as Jarecki shifts back and forth, continually introducing new information, new criticism and even recent events, all of which force the viewer to continually go back and rethink their conclusions until the only conclusion is that Capturing The Friedmans presents a situation with no absolutes. The implications of this film on the documentary genre is grand indeed, and no film has so meticulously, exhaustingly proven how impossible it is to grab a hold of a tangible, singular truth.

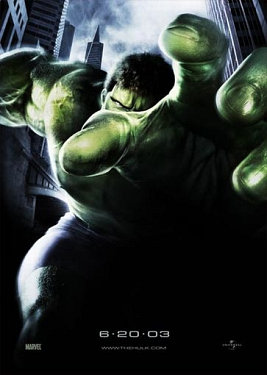

Whoah, it’s been a busy weekend, moviewise, so in addition to my treatise on The Hulk (yes, phyrephox, it’s The Hulk to me, stupid movies leaving off the proper article of a title, this is why American schoolchildren have fallen so far behind the rest of the world) I have some short comments on two other films that I managed to see this weekend, The Shape of Things and The Man Without a Past (sadly, I missed Irreversible, which I thought would play here more than one week).

The Shape of Things

This film is perhaps my favorite Neil LaBute film; it’s certainly better than his recent output, and, in my estimation, it’s also better than In the Company of Men and Your Friends and Neighbors (with the former being better than the later), the two films that LaBute’s filmmaking reputation is based upon. Why? It’s complicated, for one thing, the Aaron Eckhart character of In the Company of Men is a compelling character and a monster, but not a human monster, he’s more the shark-like predator, devouring everything without remorse (quite literally, since he’s presented as eating something in most of his scenes). Some critics have posited The Shape of Things as something of a feminine inversion of In the Company of Men, but I don’t think this is correct; this is not an instance of the shoe on the other foot, or showing that a women can be just as shitty as a corporate sociopath. For one thing the misogyny of Eckhart’s character was a cloak for his predation upon his weaker male co-worker(s). But more importantly, Rachel Weisz’s character, who is as easily as manipulative as Eckhart’s, seems genuinely ambivalent about her own machinations, unlike Eckhart’s character, who can simply shrug off his friend/coworker’s frantic phone call and go back to bed with the girlfriend he’s been cheating on for weeks. I think that Weisz’s “Evelyn” is a monster, but unlike Eckhart, she’s a human monster.

I also think that LaBute had a very different message in mind when he created The Shape of Things, encapsulated by the Hans Suyin quote that features prominently in the last, scathing scene: “Moralists Have No Place in an Art Gallery.” The way the scene plays out in front of the quote (it’s painted in large letters on the wall of the gallery) and I took it as an ironic statement, given the dynamic of the scene, the confrontation between victim and victimizer. Evelyn’s defense of her human sculpture, based on the autonomy and distanciation of art, is devoid of morals and ethics (I’d actually find it hard to believe that her art advisors would approve of her project); her internalization of that ethos has seriously retarded her ability to make the distinction between right and wrong (she’s basically a sociopath with an MFA; though the she, ultimately, does have a point about our societal concern for the surface of things, I caught myself thinking that “hey, at least [Adam] is good looking now.”) I was particularly struck by Adam’s assertion that she should be a better person, not better like him, but just better. I think that LaBute is saying that morality and ethics are central to art, and the lack of morality can lead to monstrosity (I also think that LaBute points out the difference between moralism in art and morality in art; going back to the beginning of the film and plaster-fig leaf covering the sculpture’s penis).

In general, I liked the film a lot. I generally agree with André Bazin that when filming theater, keep it theatrical, so I was glad that LaBute kept his four-part play intact and really didn’t open up the play too much (for example, leaving the drive to the beach out). Despite my hatred of Weisz’s nasally attempt at a Midwestern accent, I really liked her performance; I could readily agree with Adam’s assertion that she was a “fucking cunt,” but I also felt sorry for her. Paul Rudd was great as the naive Mormon caught in Evelyn’s web of lies, after this film and being one of the few really funny elements of this season’s Friends, he deserves more stardom. Frederick Weller, who for some reason reminds me of Barry Pepper, nailed the shallow frat-boy character, and Gretchen Mol was cute and desirable (though I have to say, that Adam and Jenny’s previous attraction kind of undercuts a central part of Evelyn’s thesis), like the girl next door. One last thing, though, what’s up with LaBute and accompanying his film with music by one group: you got the rhythmic drums of In the Company of Men, the string quartet doing Metallica covers in Your Friends and Neighbors, and Elvis Costello throughout The Shape of Things?

The Man Without a Past

Not a whole lot I want to add to this movie, phyrephox’s earlier review pretty much summed it up for me. This is actually my first real experience with Kaurismaki; it took me about 20 minutes before I shut off the video for Leningrad Cowboys Go America. Perhaps I need to revisit that earlier film, but here, Kaurismaki’s style pays off. The deadpan humor, the way everyone moves and talks so deliberately, and the expressiveness of the actor’s faces. It kind of sneaks up on you, but the movie is very funny in retrospect, without losing a certain sense of bleakness; it’s also a very sweet, simple love story between M and Irma. Here’s to the liberating effects of Rock N’ Roll!

The Hulk

Well, that was disappointing. In the past, the team of Ang Lee and James Schamus has always been money, but with their newest film, the adaptation of the Marvel comic book The Hulk, they’ve misfired. Despite Lee’s sometimes brilliant execution (of course, I particularly liked Lee’s usage of split screens and CGI to replicate the feeling of comic book panels; however, there were also the innumerable scenes of impressionistic color and twinkling lights that seemed like some kind of bad 60s avant-garde film), he was let down, for the first time in my opinion, by Schamus’s script (well, there were also two other screenwriters, but Schamus also wrote the story) which among other things was filled with rather boring exposition (the entire first act) which delayed the appearance of the Hulk for far too long, and concluded with an almost comically pretentious ending (I’m not talking about the sequel-inducing coda or the actually nice reconciliation between father and daughter Ross) which reminded me of the ending of the classic anime film Akira, as it was both turgid, murky, and incoherent (and was preceded by a bit of comically overwrought acting by Nick Nolte; for examples of good overacting in comic book films, please see Jack Nicholson in Batman and Willem Dafoe in Spider-Man).

Like Spider-Man, The Hulk was basically an origins story. How close it actually hews to the source material, well that I do not know (for some reason, with the introduction of “nanomeds” I doubt that it was really that close). My familiarity with the comics is passing at best, and I was never a devoted fan of the 70s television show (there was, however, a nice homage towards the beginning of the film, as both Stan Lee and Lou Ferrigno, had walk-on cameo roles as security guards who greeted Bruce Banner outside his lab). From my experience, unless you are going to create a television show around the origins of a particular super hero, a la Smallville, it’s best to dispense with the actual pre-superhero stuff rather quickly, just set-up the basic situations and then get with the superpowers. The Hulk takes a different path: first we get a couple of scenes about the work of Bruce’s father, David, your classic mad genius type, even with the stringy bad 70s haircut, and his experiments with regeneration on himself, which he proceeds to pass onto his son, Bruce (step one of a three, count’em, three step approach to becoming the Hulk), Bruce’s childhood, David being busted by then Major Ross, then some horrible accident (ooh, repressed trauma), then some scenes with his adopted family, then a lot of scenes of Bruce, working with his former love Betsy Ross (Jennifer Connelly, and yes, she is the daughter of David Banner’s former superior), some more plot set-up involving a gleefully smarmy military contractor, then some flashbacks about Bruce’s relationship with Betsy, then a reunion of sorts between the two Banners, and then finally the lab accident that involves both “nanomeds” and gamma radiation (steps two and three of the rather complicated three step process).

Oh yeah, things aren’t over yet, we still get more scenes of Bruce’s recuperation, more meetings between father and son, and eventually, thank the lord, an explosion of anger within Bruce that causes the emergence of the hulk. As you can see by all my usage of the word “then,” I was growing a little impatient with the film at this point, I wanted to see Hulk smash, I paid $5 to see Hulk smash; if I was wearing a watch, I would have been checking it long ago. You know, I remember that the TV show dispensed with all of this stuff in the opening credits. Now that’s efficiency. And perhaps my impatience was amplified by something else; earlier yesterday,before I went to the theater, I was rewatching the S4 Buffy the Vampire Slayer episode “Wild at Heart,” which pretty much deals with many of the same themes featured in The Hulk; an emotionally levelheaded, stoic man has his inner beast unleashed, a pure id (in the case of Buffy, it was a werewolf), and how it effects his relationship with the woman who loves him and wants to help, but who really can’t (yeah, yeah, “Wild at Heart” lacks the parent-child dynamic featured prominently in The Hulk). A bunch of television writers were able to convey almost the exact same emotional and subtextual story, in it’s entirety, within 45 minutes (with a sense of humor, something pretty much lacking in The Hulk); it basically, took The Hulk that long to set up their basic premise. Shroomy angry...Shroomy smash....

Oh yeah, how was the smashing? Well, amazingly, nobody seemed to die, except for smarmy Pentagon contractor guy, even though the Hulk managed to chuck an M-1 Tank a good 1000 feet, or knock down several helicopters. The hulk did rip up a bunch of buildings real good, and there was a knockout, drag down fight between the Hulk and a pack of hulkified, mutant dogs (including one of the film’s few truly funny conceits, a mutant French poodle) which seemed to pay homage to the treetop fight in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, but left me thinking about the fate of our poor national treasures, the redwood tree, which were felled during the battle. Basically, even with Lee’s choice to replicate comic book panels, the action was not all that interesting, it lacked a dynamism, and I guess a bit of “finesse” (yes, we talking about the Hulk, so this request is kind of paradoxical). The Hulk is like the proverbial bull in the china shop, nothing is safe but a lot of mindless destruction gets kind of boring, especially when there is little to differentiate it from other scenes of, well smashing. Plus, a CGI effect fighting another CGI effect is usually less than thrilling. Which reminds me, since I mentioned it, I was actually pleasantly surprised with the CGI creation of The Hulk; I had serious doubts when I first saw the trailers during the Superbowl, but I guess the filmmakers were correct, the SFX were not ready at the time. The Hulk is no Gollum, but then again, he’s no Jar Jar either; he looked less fake and more expressive than I thought he would, which is a definite plus. When David Banner reaches out and touches the cheek of his mutant son, it seemed like Nolte was actually touching something, very nice. The one thing I didn’t like about the Hulk, was his jumping ability; it wasn’t that I did not like the fact he could jump several miles at a time, it was the direction. It wasn’t like I was expecting the grace of Spider-Man, but the jumping scenes were staged rather boringly, basically helicopter shots or extremely long shots with superimposed CGI. You really get no sense of movement from the Hulk’s perspective. Another missed opportunity.

Actually, as conceived in the film, the Hulk character, purely in terms of characterization, was a bit disappointing. Unlike most super hero movies, the Hulk is not a hero, like Superman or Spider-Man, or a vengeful anti-hero/hero, like Batman or Daredevil, he’s motivated purely by anger and the vestigial love for Betsy that he feels (he also seems to have some sort of residual social conscience, as he diverts an errant F-22 from striking the Golden Gate Bridge). In many ways, he’s like King Kong, though in that classic film, I always got the impression that Willis O’Brien’s stop motion creature wanted to boink Fay Wray; the Hulk and Betsy are a little more chaste. Since the “beast within” and love-story are kind of shortchanged by the screenplay, most of the conflict comes from the strained relationships between father and son, and father and daughter. Of those two sets of relationships, only the one between Ge. Ross and Betsy is emotionally involving, the other one, between David and Bruce is too fucked up and ludicrous for anyone to really care. Actually, the crux of that relationship is the remembering of a repressed memory (easily guessed by the viewing audience), the recovery of which leads to a less than tragic result. On the otherhand, the relationship between the emotionally distant Gen. Ross and his daughter, Betsy, is more effective, because you can tell that the General actually cares about his daughter, and at least acts on what he perceives to be her best interests, while, with a few exceptions, David Banner is a crazy loon with bad hair.

Sam Elliot, sporting a mustache you could scrub pots with, steals the movie as the steely, hard-edged, yet compassionate (though he hides it well) General Ross; you can look through his reserved facade and see how he tentatively reaches out to his alienated daughter, and even how he feels guilt about what happened to the young Bruce Banner (he also is very effective at barking out orders). As Roger Ebert noted (I believe), Jennifer Connelly, as Betsy, basically reprises her role from A Beautiful Mind, though, other than guide Bruce through some token psychoanalysis, is given pretty much nothing to do except gaze longingly, fear or in sorrow at Bruce, the Hulk, and/or her father (hey, I’m not saying that Kirsten Dunst had a lot to do with the role of Mary Jane in Spider Man, but at least she had some inner conflict to deal with). Eric Bana displays little of the charisma evident in Chopper, though I guess he does OK in the role of button-downed, repressed David Banner; it’s more or less a failure of the screenplay, but the film doesn’t convey the sense of both the difference and the similarity between the man and the monster (and a scene of Bruce gazing at a mirror and seeing the visage of the Hulk doesn’t quite cut it). As I said earlier, Nick Nolte, as David Banner, hilariously over acts (well, at least until that becomes dull), by using his trademark, hoarse whisper or by full on ranting and raving; it doesn’t help that David Banner’s mental state and motivations are inconsistent, and at times even contradictory. I know, mad scientist, and what not, but the characterization just left him incoherent (using my earlier examples, Jack Nicholson as the Joker, and Willem Dafoe as Osbourne/The Green Goblin, were mad as a hatter too, but they were still pretty focused). And then we enter the quasi- Akira territory, which is neither profound or interesting.

Perhaps I’m a bit too harsh on the film, but I expect more out of Ang Lee and James Schamus; I like that the films based on Marvel Comics are at least trying to find name directors to work on their films (though looking at the IMDB.com listing for the next big Marvel film, The Punisher, the teaser trailer of which preceded The Hulk, leaves me less than enthused; and I mean, how can we so soon forget the 1989 Punisher film starring Dolph Lundgren, Lou Gosset Jr., and Jerome Krabbe? Also, from this, it looks like the first tier comic book character get the good directors, while the second tier guys like The Punisher and Daredevil get newbies and second tier directors). However, I think these same top tier talents need to reign in their artiness. I’m not saying that they have to dumb down their work, but they need not weight it down with leaden pretension, nor do they have to attempt to make everything seem plausible. It’s not necessary to create such an elaborate back story on how the Hulk was created, nobody needs it, nobody goes to a comic book film without suspending some disbelief (and nobody cares except for hardcore fanatics, who are likely to be pissed off any ways by the liberties that the film takes with the comic books). I think the best comic book films benefit from a more straight-ahead, linear approach, using (I hate to describe it this way) rather “simplified metaphors” (but not simplistic) to create mythic and emotional resonance in the audience. A perfect case in point, Spider Man.

|