|

Joker Recommends

|

-Top 20 List

-House of Flying Daggers

-The Aviator

-Bad Education

|

|

Yun-Fat Recommends

|

|

-Eight Diagram Pole Fighter

-Los Muertos

-Tropical Malady

|

|

Allyn Recommends

|

|

-Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

-Songs from the Second Floor

|

|

Phyrephox Recommends

|

-Top 20 List

-Design for Living (Lubitsch, 1933)

-War of the Worlds

-Howl's Moving Castle

|

|

Melisb Recommends

|

-Top 20 List

-The Return

-Spirited Away

-Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter...And Spring

|

|

Wardpet Recommends

|

|

-Finding Nemo

-Man on the Train

-28 Days Later

|

|

Lorne Recommends

|

|

-21 Grams

-Cold Mountain

-Lost in Translation

|

|

Merlot Recommends

|

-Top 20 List

-The Man on the Train

-Safe Conduct

-The Statement

|

|

Whitney Recommends

|

|

-Femme Fatale

-Gangs of New York

-Grand Illusion

|

|

Sydhe Recommends

|

|

-In America

-Looney Tunes: Back In Action

-Whale Rider

|

|

Copywright Recommends

|

Top 20 List

-Flowers of Shanghai

-Road to Perdition

-Topsy-Turvy

|

|

Stennie Recommends

|

Top 20 List

-A Matter of Life and Death

-Ossessione

-Sideways

|

|

Jeff Recommends

|

|

-Dial M for Murder

-The Game

-Star Wars Saga

|

|

Lady Wakasa Recommends

|

|

-Dracula: Page from a Virgin's Diary

-Dr. Mabuse, Der Spieler

-The Last Laugh

|

|

Steve Recommends

|

-Top 20 List

-Princess Raccoon

-Princess Raccoon

-Princess Raccoon

|

|

Jenny Recommends

|

|

-Mean Girls

-Super Size Me

-The Warriors

|

|

Lons Recommends

|

|

-Before Sunset

-The Incredibles

-Sideways

|

|

(c)2002 Design by Blogscapes.com

|

The Blog:

|

Time of the Wolf

After leaving the city to go to their summer cabin a French family of four discovers a distressed family already at their place, armed with a rifle and in a near hysteric need for supplies. The intruders seem more desperate than crazy but just when attempts to placate them seem to be successful the gunman unexpectedly guns down the French husband.

This event sets the newly widowed Anne (Isabella Huppert) and her two children Eva (Anaïs Demoustier) and Ben (Lucas Biscombe) adrift in the French countryside. A mysterious catastrophe in France-if not the world-seems to have occurred, stifling the flow of supplies to urban centers and d ispersing the population out of cities. Though the film suggests that many others are sharing the same fate, Anna’s small family is dwarfed by the oppressively empty, foggy landscape making them feel isolated even if they are not. Forced into the forbidding countryside to fend for themselves the family turns back to the town for help. But finding the villages shut up and the occasional inhabitants unforgiving or unresponsive,the family goes back to roving the empty land for shelter, food, and hoping for some definitive, God-like event to save them from their seemingly intangible fate. ispersing the population out of cities. Though the film suggests that many others are sharing the same fate, Anna’s small family is dwarfed by the oppressively empty, foggy landscape making them feel isolated even if they are not. Forced into the forbidding countryside to fend for themselves the family turns back to the town for help. But finding the villages shut up and the occasional inhabitants unforgiving or unresponsive,the family goes back to roving the empty land for shelter, food, and hoping for some definitive, God-like event to save them from their seemingly intangible fate.

A passing train provides brief hope for Anne and the children, but when it fails to stop for the screaming family they follow the tracks and find a small group of people holed up in a station, waiting for salvation from a train that may neither stop nor even pass them by. Within the group is a vague semblance of societal relations, with the requisite enforced rules and subsequent fits of conflict, frustration, hysteria, and resignation involved. 14-year old Eva attempts to befriend a roving teenage boy (Hakim Teleb), trying both to find a friend amongst the selfish adults as well as compassionately trying to draw the boy back to society. The group gradua lly allows itself to fall into a rhythm of daily life despite the arbitrariness of its survival, which remains in constant flux as they deal with lack of supplies, group conflict, inner turmoil, and the abstract dread that pervades the world around them. lly allows itself to fall into a rhythm of daily life despite the arbitrariness of its survival, which remains in constant flux as they deal with lack of supplies, group conflict, inner turmoil, and the abstract dread that pervades the world around them.

The spare, unexplained post-civilization France of Michael Haneke’s Time of the Wolf is one that serves no direct allegorical purpose. Instead, the push and pull of the ambiguous situation, oscillating between misanthropy and humanism, glides along in an evocative, precise enactment of the tensions of a nondescript family taken far out of context.

The easy irony of Haneke’s film is that much of the pain the family suffers is a common one. It is within this reading that the film bares strong similarity to Stanley Kubirck’s 1980 film The Shining, which plopped an average family into a isolated vacuum surrounded from without and within by the burdens of myth and history. The terror-drama that thereafter played out was one that simply extrapolated from the family’s malignant inner disorder and manifesting through the environmental motivations of the “haunted” surroundings. Anne’s family is much the same way, the post-apocalyptic landscape serving merely as a literalization of the tumultuous problems within her discentered family.

All three remaining members of the family have difficulty communicating and reconnecting with each other, an alienation only underlined by the vacuous grey countryside through which they search and cold concrete interior of the train station that soon becomes their home. Anne, with her husband gone, has a crash course in single-motherhood, teetering on the bring of hysteria trying to deal with her dual responsibilities for familial survival and providing nurturing comfort and love.

10-year old Ben hams up after his father’s death and acquires the reticent mystery that all boys that age seem to have when they are moody and silent. Like Danny in The Shining he also acquires an element of the supernatural-after his father’s death Ben has emphatic nosebleeds that occur when the boy reaches a level of understanding of the wretched situation of his family.

The daughter’s path through the countryside is the most touching, not the least because of Demoustier’s curious, compassiona te face and Eva's blossoming social maturity and responsibility. The teen's attempts at getting to the runaway youth are moments of the film’s purest kindness, especially in light of an understated theme of latent racism within the multicultural European populace. The teenage couple's quarreling speaks textually for the repressed tension that generally remains unspoken between the isolated adults of the film, showing both their best and worst sides, the means for fixing the problems and the problems themselves. te face and Eva's blossoming social maturity and responsibility. The teen's attempts at getting to the runaway youth are moments of the film’s purest kindness, especially in light of an understated theme of latent racism within the multicultural European populace. The teenage couple's quarreling speaks textually for the repressed tension that generally remains unspoken between the isolated adults of the film, showing both their best and worst sides, the means for fixing the problems and the problems themselves.

Although the family is wrestling with common issues, with the help of chilling photography by Jürgen Jürges Time of the Wolf presents a layer of latent primality to the scenario that mystifies the tale in a similar, though more "believable" way as The Shining. It is this mystery that helps individualize the normalcy of the family, making their tale at once ordinary and highly specialized. Often Haneke evokes the idea of the family as an opaque blade trying desperately to cut its through the densest haze, a disturbing metaphor both for the generic family and any extrapolations of the film's premise to Europe or humanity itself.

What stands out most strongly in the haze, stronger really than any of the human elements

in the story, is the vibrant, primal attraction of fire. Fire is used to find the lost and wandering, as well as attracting scavengers to its promising glow. Whether sparks or bonfires, the flames of Time of the Wolf seem hopeful, as if a promise of refuge, communication and social continuation. At the same time fire is infused with the powers of rebirth. Refugees stuck at the station speak of a binary paganism, where belief resides in a group called the Just, which, acco rding to belief, are either a group of copulating mystics who prolong humanity or a group of martyrs who sacrifice themselves in bonfires for the salvation of others. Though most are unbelieving, the eerily life of the fires, which provide the only vibrancy and enduring image in the whole picture, seem to contain a power which speaks for the hope inside these people. The few flames ignited seem to speak for a deep, scattered understanding of the human condition that can gradually be felt pulsating through the characters despite their often callous behavior. In them, through the flames, can be felt the power of humanity, and in that comes the power to overcome Haneke's so-called time of the wolf. rding to belief, are either a group of copulating mystics who prolong humanity or a group of martyrs who sacrifice themselves in bonfires for the salvation of others. Though most are unbelieving, the eerily life of the fires, which provide the only vibrancy and enduring image in the whole picture, seem to contain a power which speaks for the hope inside these people. The few flames ignited seem to speak for a deep, scattered understanding of the human condition that can gradually be felt pulsating through the characters despite their often callous behavior. In them, through the flames, can be felt the power of humanity, and in that comes the power to overcome Haneke's so-called time of the wolf.

The Bourne Supremacy and The Loneliness of Matt Damon

Woe be the cinema of Matt Damon, it is a one of loneliness and rejection. Time and time again the actor has gravitated to roles of outsiders unable or unwanting to cope with assimilation into society proper, and  is often burdened with the tragedy of having to kill or sacrifice what he holds dear simply to live another day of pensive alienation. The trend can be traced through a startling amount of his work: an anonymous youth in The Talented Mr. Ripley, he sought to be noticed by stealing the identity of a wealthy American playboy; he played a dejected and down and out WWI veteran in The Legend of Bagger Vance; and even comedic roles show a similar pattern, for example the less confident half of a Siamese twin in Stuck on You and in a Kevin Smith comedy Damon fills the role of a rejected angel, banished from Heaven by God in Dogma. The constantly reprised character type even went so far as to try to find a place in the wilderness in Gus Van Sant’s Gerry. Playing a Gen-Xer arbitrarily trying to reconnect with nature Damon finds himself just barely able to survive, and once again having to sacrifice someone close to him, leaving the character not just alone but burdened with knowledge that he is not fit to exist anywhere on this earth.

And so it is only fitting that Damon has decided to attach his name Connery-style to the adaptations of Robert Ludlum’s Jason Bourne novels. Bourne was part of a CIA operation to groom the perfect assassins, but, as exposed in The Bourne Identity Bourne’s first mission went awry and he suffered amnesia. With no known past Bourne is bewildered by his characterlessness. Pushed to the fringe of society by CIA assassins he knows neither the comfort of human acceptance nor awareness of his own identity, leaving the man alienated where it hurts the most-knowledge of self. In the previous film he fought off attempts to terminate his services and dropped off the map. The Bourne Supremacy picks him up living in a tourist town in India with Marie  (Franka Potente), the girl he fell for in the first film obstensibly because she too had no place to call her own. But Bourne is played by Matt Damon, whom we have now concluded perpetually plays the cinematically homeless, so when the trouble starts the first thing that is taken away is his confidence in his life, his love, and his home. To erase traces of an old crime being investigated by the CIA a corrupt Russian businessman has an assassin (Karl Urban) frame Bourne for two killings and then kill Bourne himself, sending the clueless CIA off on a trail for a dead man and evidence that does not exist. Bourne may have settled down but he has not gone completely soft. His skills saves his own life at the cost of his love, leaving Bourne, and Matt Damon, with the only option of traveling the globe to find out who is trying to kill him and why.

Paul Greengrass replaces Doug Liman in the director’s chair of the Bourne sequel, but keeping the same composer and cinematographer the film retains an aesthetic consistency unknown to most continuing studio properties. Greengrass’ touches are still noticeable in The Bourne Supremacy-handheld camerawork, overlapping editing, handsome framing, and echoes of Bloody Sunday’s interest in logistical communication-but like Terence Young in the first Bond films the director’s main accomplishment is keeping the series consistent in mood and narrative. For the Bourne series this means keeping the roving tone, as if Bourne is a shark who must keep moving or else perish; keeping the grey-minimalistic aesthetic which drains the European locations of their life, charm, and friendliness in the eyes of Bourne; a  nd containing not action per se but short bursts of realistic, professional combat, followed some kind of elaborate chase sequence where Bourne is not so much escaping as he is being run out of town.

The differences then between the first film and the second are surprisingly small. Bourne is still escaping the clutches of CIA headhunters-Brian Cox returns as a cynical, fleshy vet full of evasive warnings and Joan Allen unexpectedly turns up as a green but eager department head unaware of the depth of Bourne’s talent-and at the same time is trying to figure out why his existence is being contested once again. Instead of determining his identity Bourne has gotten more specific, trying to hunt down the meaning in obscure, elliptical nightmares that plague him daily. But Bourne’s hunt for his oppressors, his pursuit for true and their chase of him seem merely an extension of Bourne’s own innate self-mystification, his confusion over his existence’s meaning and its purpose, neigh even its validity.

Such a reading is deep within the fairly superficial text, for the film is lean, but like The Bourne Identity one gets the overwhelming feeling that Bourne’s search is one to keep him busy, to distract himself from the knowledge that he really has no understanding  of himself, that all he knows is that the world rejected him for some flaw in himself of which he is constantly unaware. The one person who would argue for him, perhaps provide a reason for existing through mutual compassion and partial understanding is Potente’s Marie, who blessed the first film with a sweetness and unlikely chemistry with Damon, but who is quickly taken away from Bourne, leaving Damon once again on his own to fend for his life in a world that inexplicably doesn’t want him. The Bourne Supremacy may not be the ultimate of Damon’s alienation-Minghella and Van Sant’s films probably being the most stylized, interesting, and effective statements for the actor’s reprising character-but it is a continuing mainstream translation that fully revels in the actor’s career patterns.

As for the film, it acquits itself adequately, just like its prequel. Without Potente on board (or Clive Owen for that matter) and with Damon essentially reprising much of the same character arc as the first film-with the notable exception of more determination, less confusion-the highlights of the film end up being the incredibly efficient action sequences. Greengrass’s eye for action is mature and interesting. He takes the clear-minded, highly stylized supreme bitch fight between Vivica A. Fox and Uma Thurman in Kill Bill Volume 1 and restages a similar home-invasion between Bourne and an ex-assassin compadre. The director strips the scene of any stylization and turns in a brutal, confused,  claustrophobic sequence of close-quartered combat. He applies a similar visual rationale to a later car chase, using finely tuned, rhythmic editing to turn the chase into a veritable back and forth boxing match between cars. Disappointingly the film is still more thriller than action piece, making the assumption that Bourne’s continuing identity crisis has enough depth for the movie to ride on with a low fights-per-minute ratio. Again and again the film supports the notion that Bourne’s never-ending search for meaning in his life really just translates into Damon trying to keep active, trying to integrate his long-standing character type back into society through obtaining self-knowledge. The efforts aren’t particularly exciting, as Bourne and the film indulges in petty repressed memories instead of allowing Bourne the more fruitful track of determining his current character rather than a past entity. Tracking down an old assassination and then trying his darndest to tack moral meaning onto his past life as a killer still feels like arbitrary things to keep Bourne busy. While this is a simultaneous flaw in the movie’s entertainment value and Bourne’s earnest development as a continuing character, it is entirely in tune with the Damon oeuvre. But if the next Bourne film retains consistency in both style and plot mechanics as the previous two tedium will set in all the more quickly, and unless Damon decides to finally give his character a deeper, stronger attempt to either assimilate or comprehend his banishment we will be stuck with a series of thrillers getting shorter on the thrills and redundant in content.

Oasis

It was ironic that I almost missed this afternoon’s screening of the Korean film Oasis due to Madison’s Gay Pride Parade. Helmed by novelist turned writer-director Lee Chang-dong, Oasis tells an unlikely love story against the backdrop of society’s disapproval. Sol Kyung-gu plays Hong Jong-du, a recently released convict whose irresponsibility and lack of social mores is seen as an embarrassment and burden by his urban, middle-class family, especially his judgmental elder brother Jong-il (though it’s never really elucidated in the film, there is clearly something “off” about Jong-du, who is, in some way, developmentally disabled). The bulk of the film concerns Jong-du’s growing relationship with a young woman named Han Gong-ju, played by actress Moon So-ri. To say their relationship is unlikely is an understatement as Gong-ju suffers from severe cerebral palsy, Jong-du went to jail for killing her father in an auto-accident (they meet when Jong-du nonchalantly attempts to make amends with the Han family), and there first real meeting ends in Jong-du’s attempted rape of a terrified Gong-ju (that is, until Jong-du’s brain catches up with his body and he is stricken with guilt and remorse). Despite all that, the isolated and lonely Gong-ju reaches out to the disaffected Jong-du one night, and he reciprocates with something that Gong-ju has rarely experienced. He treats her like a normal person, whereas her family treats her like a leper (they exploit her disability to get themselves a brand new apartment while leaving her all alone in their old, rundown place) and the neighbor who is being paid to watch over her can barely bother, even using Gong-ju’s apartment for an afternoon tryst with her lover.

At first, I didn’t think I was going to like Oasis. I thought the lead actors’ performances were somewhat, annoying mannered; Sol’s Jong-du shuffles around throughout the film, and he loudly sniffles practically throughout the entire film, and Moon So-ri, who is not disabled, gives a bravura impression of someone afflicted with cerebral palsy, though at first I was always cognizant that she was performing. There was that, and the entire attempted rape, which was appropriately disturbing, and which gave me a queasy feeling when their relationship began in earnest. However, as the film went along (and at 2 hours, 13 minutes long, the film takes its time developing the characters and their various relationships), it slowly drew me in as I became invested in their relationship. Jong-du’s lavish attention, growing affection, and refreshing patience makes him an increasingly sympathetic character (not to mention that we later learn the truth behind his latest conviction), and allows Gong-ju to open up, so I could focus more on the character than the actress’s physical performance. Their relationship is a memorable collections of simple moments captured by Lee Chang-dong’s observational yet sympathetic camera (thank god, for a film dealing with the disabled, it never degenerates into schmaltz, never even coming close) : conversations in her apartment; doing the laundry; singing; enjoying the crisp, winter air on the rooftop of her apartment building; riding the subway; ordering noodles; talking on the phone. The accretion of moments and observations is a welcome respite from the couple’s separate familial problems, which worsen over the course of the film, especially after Jong-du’s family learns of his relationship with Gong-ju in one of the most uncomfortable scenes of the entire film.

Lee makes a crucial stylistic choice, which was perhaps my favorite aspect of the movie, he allows us inside of the mind of Gong-ju, who, of course, is the character who has the most trouble communicating in general. Our first introduction to Gong-ju is actually of an angelic dove fluttering around her apartment to the soft sounds of someone quietly singing, Gong-ju remaining out of frame. When we finally glimpse Gong-ju we learn that she uses a hand mirror to reflect the sunlight onto the walls and ceiling of her drab apartment, using her imagination to turn the motes of light into birds and butterflies, which despite how it sounds, is not cloying or precious. Much more importantly, Lee integrates lyrical fantasy sequences from Gong-ju’s perspective seamlessly into the film, veering from realist (on the subway, Gong-ju watches a couple talk and flirt, and imagines herself as a woman with complete control of her body, mimicking the woman across the car by slapping the inattentive Jong-du with a plastic water bottle) to the magical realist (the tapestry from which the film takes its title comes alive in her living room). All the actorly tics melt away and we are forced to contend solely with a vibrant young woman, the gulf between her uncooperative body and her inner life adding the right bit of poignancy and sadness to the proceedings.

This gulf comes to a head in the final sequences of the film, when Gong-ju asserts herself and asks Jong-du to sleep with her. The scene starts out humorously, as Jong-du at first does not comprehend her request, and then, in an inversion of their first encounter, is somewhat reluctant to do so. Their lovemaking is awkward but tender, Jong-du always inquires if he is hurting her (truth be told, it was hard to tell), which she answers by clearly drawing Gong-ju closer to her. Unfortunately, her brother and sister-in-law pick that time to make one of their infrequent visits. Finding the two of them in bed with each other horrifies her family, who can not comprehend Gong-ju as a sexual being, and immediately jump to the conclusion that he is raping her. He’s arrested by the police and taken to the jail; Gong-ju is so emotionally flustered that her spasms worsen, and she is unable to tell the police and her family what was actually happened. Pretty much ignoring her, they simply proceed to report what they think happened. She becomes so frustrated that she violently pushes her wheelchair back into a metal filing cabinet over and over again, to the shock of everyone around her. For his part, Jong-du does not even attempt to defend himself, and his family pretty much disowns him, though his younger brother makes a feeble attempt to defend him when Gong-ju’s brother tries to shake them down.

Jong-du does manage to escape from police custody, and makes his way back to Gong-ju’s apartment in what I think it one of the most touching and poetic endings (albeit crazy) to a film that I saw this year. Jong-du climbs the tree that looms outside Gong-ju’s bedroom and begins to maniacally saw off the tree limbs that used to cast menacing shadows on her bedroom wall (it’s a recurring motif used throughout the film), while the bewildered police watch from below, dodging fallen branches and sipping coffee. Gong-ju, unable to yell out to her lover, instead struggles to lift her radio up to the window sill, loudly blaring her favorite music out the window. The whole thing looks crazy to those looking from the outside, and the cranky comments from all the neighbors can attest to that fact, but Lee is able to pull off this unusual expression of love without falling into sentimentality.

The film itself ends with a short coda. We see Gong-ju slowly cleaning her apartment as we hear Jong-du’s voice on the soundtrack, narrating a letter written to her from prison. He’s still hopeful for a future with her, and as the camera silently observes her slowly sweeping up her living room floor, we see that her relationship with Jong-du has invested her with a lasting sense of independence.

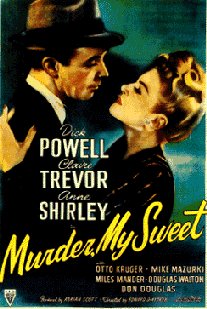

Shadows, Lies & Private Eyes – Film Noir DVD Box Set from Warner Home Video Dude, this box set rocks. Five essential film noirs, all beautifully restored, all featuring full-length commentary tracks.  Murder, My Sweet, 1944 (directed by Edward Dmytryk; starring Dick Powell, Claire Trevor, Anne Shirley). Dick Powell, previously best-known to movie audiences as the weedy tenor in Busby Berkeley musicals of the '30s, pulled off one of the greatest career redefinitions ever with his tough, smart, cynical portrayal of Philip Marlowe. To put it in modern terms – imagine Clay Aiken being cast as the next James Bond. And pulling it off. Yeah, it was that astonishing. Murder, My Sweet was based on Raymond Chandler's novel Farewell, My Lovely, which finds Philip Marlowe investigating a stolen jade necklace, which leads to the murder of a society leech. Murder, My Sweet, 1944 (directed by Edward Dmytryk; starring Dick Powell, Claire Trevor, Anne Shirley). Dick Powell, previously best-known to movie audiences as the weedy tenor in Busby Berkeley musicals of the '30s, pulled off one of the greatest career redefinitions ever with his tough, smart, cynical portrayal of Philip Marlowe. To put it in modern terms – imagine Clay Aiken being cast as the next James Bond. And pulling it off. Yeah, it was that astonishing. Murder, My Sweet was based on Raymond Chandler's novel Farewell, My Lovely, which finds Philip Marlowe investigating a stolen jade necklace, which leads to the murder of a society leech.

Like a lot of Chandler mysteries, it takes the audience a lot longer to piece together what the hell's going on than it takes Marlowe, but it doesn't matter because the dialogue is so great, and the characters who keep coming and going are so well realized. Claire Trevor kicks ten kinds of ass as the femme fatale Helen Grayle. I personally prefer Powell's breezy, relaxed Marlowe to Bogart's uptight take on the role. But then, Bogart's never been a favorite of mine anyway. Anne Shirley as the love interest, the "good girl," is sharp and keeps Marlowe on his toes – a good match for him.

The commentary by Alain Silver is a good listen. I'm pretty critical of commentaries anyway, most of the time I want the person to shut up so I can hear the movie, but Silver was full of good insights, particularly regarding the camera work and the lighting.

The Asphalt Jungle, 1950 (directed by John Huston; starring Sterling Hayden, Sam Jaffe, Louis Calhern, Jean Hagen). ASPHALT JUNGLE stars Sterling Hayden as a big lumbering threatening thuggish mug of a guy involved in a diamond heist, masterminded by the flawless Sam Jaffe. Everyone in this movie is great -- Louis Calhern as the weak-willed upper-class guy who's out of his league; Jean Hagen as Hayden's moll, Whitmore, Jaffe, and of course Marilyn Monroe as Calhern's mistress. The weakest link is really Hayden, who's great in the role of a big lumbering threatening thuggish mug, but towards the end when Dix is running for home and starting to fall apart, Hayden's monotone dead-eyed delivery doesn't really do it for me. The Asphalt Jungle, 1950 (directed by John Huston; starring Sterling Hayden, Sam Jaffe, Louis Calhern, Jean Hagen). ASPHALT JUNGLE stars Sterling Hayden as a big lumbering threatening thuggish mug of a guy involved in a diamond heist, masterminded by the flawless Sam Jaffe. Everyone in this movie is great -- Louis Calhern as the weak-willed upper-class guy who's out of his league; Jean Hagen as Hayden's moll, Whitmore, Jaffe, and of course Marilyn Monroe as Calhern's mistress. The weakest link is really Hayden, who's great in the role of a big lumbering threatening thuggish mug, but towards the end when Dix is running for home and starting to fall apart, Hayden's monotone dead-eyed delivery doesn't really do it for me.

The story is tightly plotted and a prototype for so many heist caper films, well-directed by John Huston and touching on many themes that are . Great movie, but I recommend skipping the commentary by Drew Casper, which is deadly dull. However, parts of the commentary are excerpted from an interview with James Whitmore talking about his experiences making the film – those are worth hearing.  Out of the Past, 1947 (directed by Jacques Tourneur; starring Robert Mitchum, Jane Greer, Kirk Douglas). Robert Mitchum is Jeff Bailey, formerly Jeff Markham, an ex-private eye who's run afoul of a former client and has gone into hiding in a small California town and trying to make a new life for himself. As the title might suggest, a visit from an old acquaintance leads him back to his old life to take care of some unfinished business, involving that ruthless former client (Kirk Douglas), an old flame (Jane Greer), and an unsolved murder. Out of the Past, 1947 (directed by Jacques Tourneur; starring Robert Mitchum, Jane Greer, Kirk Douglas). Robert Mitchum is Jeff Bailey, formerly Jeff Markham, an ex-private eye who's run afoul of a former client and has gone into hiding in a small California town and trying to make a new life for himself. As the title might suggest, a visit from an old acquaintance leads him back to his old life to take care of some unfinished business, involving that ruthless former client (Kirk Douglas), an old flame (Jane Greer), and an unsolved murder.

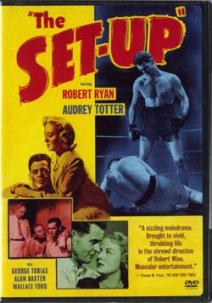

The photography (by Nicholas Musuraca) is breath-taking. I rarely care about or even notice cinematography (unless it's a movie like Dances With Wolves where the pretty pictures are a nice distraction from a dull film), but I definitely noticed in this case. It helped that the print was so flawless, I suppose. Robert Mitchum is an actor I can usually take or leave, but I was very impressed by him in this, a very easy-going demeanor covering a tormented past. Kirk Douglas does his menacing tough guy thing as the mobster who won't let Bailey go, and Jane Greer is great as the poisonous and two-faced dame. However, despite the high praise, I must admit that I fell asleep in front of this movie about three times. I really think that was more to do with me than the movie, given that I can't think of much to criticize.  The Set-Up, 1949 (directed by Robert Wise; starring Robert Ryan, Audrey Totter, Alan Baxter). Robert Ryan is Bill "Stoker" Thompson, a boxer near the end of his career, and Audrey Totter is Julie, his long-suffering wife who wants nothing more than for her husband to hang up his gloves for good before he takes one punch too many. Unbeknownst to Stoker, his manager has made a deal with a gambler to throw the big fight tonight (Tiny, the manager, doesn't see any point in telling Stoker about it, figuring he'll lose anyway, so why not just keep Stoker's share of the dough?). Stoker surprises everyone, including himself a little bit, when he wins the bout, then has to take the consequences from the gambler. The Set-Up, 1949 (directed by Robert Wise; starring Robert Ryan, Audrey Totter, Alan Baxter). Robert Ryan is Bill "Stoker" Thompson, a boxer near the end of his career, and Audrey Totter is Julie, his long-suffering wife who wants nothing more than for her husband to hang up his gloves for good before he takes one punch too many. Unbeknownst to Stoker, his manager has made a deal with a gambler to throw the big fight tonight (Tiny, the manager, doesn't see any point in telling Stoker about it, figuring he'll lose anyway, so why not just keep Stoker's share of the dough?). Stoker surprises everyone, including himself a little bit, when he wins the bout, then has to take the consequences from the gambler.

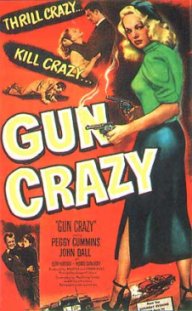

Slight story, but a good hook – the movie plays out in real time, so essentially the audience sees everything that happens to Stoker during this fateful 90 minutes of his life. As a result, the pace drags a little at the beginning, but before you know it, you're pulled into the boxing ring with the guy and hanging on every second. The boxing scene is intense – certainly not as brutal as Raging Bull, but Ryan's training as a former boxer shows. Ryan is good as the likeable palooka Stoker Thompson, and Audrey Totter makes a very sympathetic Julie. The commentary on The Set-Up is by director Robert Wise and Martin Scorsese – haven't had a chance to listen to it yet but I'm very much looking forward to it.  Gun Crazy, 1949 (directed by Joseph H. Lewis; starring John Dall and Peggy Cummins). Low budget B-grade noir from King Brothers Productions, released through United Artists, starring John Dall and Peggy Cummins as precursors to Beatty and Dunaway's Bonnie & Clyde. Dall plays Bart, who is, like the title says, "gun crazy" – from a very young age, he's always been obsessed with guns. As a youngster he believes that shooting a gun is the only thing he does well, so he does it a lot. However, when he kills a baby chick, he is inconsolable and vows never to kill another living thing. Fast-forward a number of years, after a stint in juvy and the Army, Bart takes up with Annie, a sharp-shooter from a traveling carnival show. She's addicted to easy money and the thrills, he's addicted to her. The result is a spree of robberies, culminating in "one last big job." Gun Crazy, 1949 (directed by Joseph H. Lewis; starring John Dall and Peggy Cummins). Low budget B-grade noir from King Brothers Productions, released through United Artists, starring John Dall and Peggy Cummins as precursors to Beatty and Dunaway's Bonnie & Clyde. Dall plays Bart, who is, like the title says, "gun crazy" – from a very young age, he's always been obsessed with guns. As a youngster he believes that shooting a gun is the only thing he does well, so he does it a lot. However, when he kills a baby chick, he is inconsolable and vows never to kill another living thing. Fast-forward a number of years, after a stint in juvy and the Army, Bart takes up with Annie, a sharp-shooter from a traveling carnival show. She's addicted to easy money and the thrills, he's addicted to her. The result is a spree of robberies, culminating in "one last big job."

Light on plot, but some great camera stuff going on -- there's one scene of a bank robbery shot in one continuous take (starting from as they're driving through town to the bank, and up through the getaway) from the backseat of the getaway car. Reportedly, it was done in one take and all the dialogue was improvised. The effect is thrilling, it really throws the viewer into the action. Overall, Warner Home Video's done a great job with this box set. The prints are all crisp and clear – Out of the Past looks like it could have been shot yesterday. If you have even a passing interest in film noir, this collection is essential.

|

|